Three years ago, my children –– who were two and a half and four at the time –– decided that the perfect birthday present for me was a chicken costume.

I’m not making this up.

They came up with this idea all by their precious little selves, in spite of all the exposure they'd had to mass produced coffee mugs and ties emblazoned with the words “World’s Greatest Dad.”

Only one came close. And you know what’s weird? I got it the same year.

But before I can share it with you, I have to give you a little backstory.

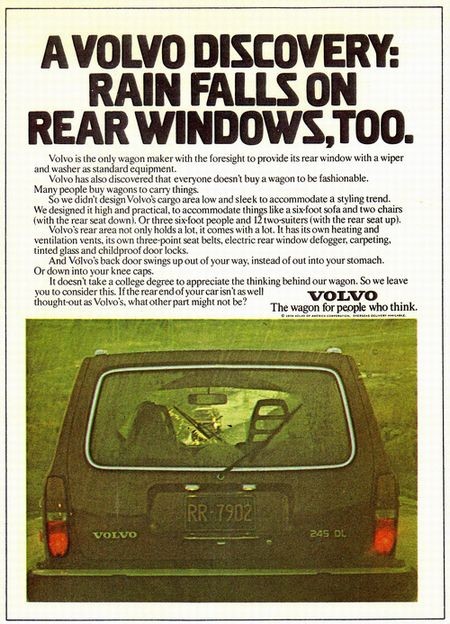

Back in the 1970s and 80s, Ed McCabe was heralded as one of, if not the greatest copywriter ever in the history of advertising. He created legendary ads for Volvo, Perdue, Nikon, Cutty Sark, and a bunch of other brands. And I had the incredible good fortune to work for him.

|

| An ad Ed did in 1973. Makes you feel like a schmuck for not buying a Volvo, doesn't it? |

You weren't hired to work for Ed, you were chosen. And we who had been chosen went to a lot of trouble to be sure we were worthy of the grace we had received. We behaved more like acolytes than employees, studying the Gospel According To Ed and exhorting those who weren’t pure of faith to see the light, quoting him the way young Chinese communists used to quote Chairman Mao.

“A good ad makes you feel like a schmuck for not buying the product.” was one of my favorites.

Over the years I've found that there were other ways to be righteous in advertising and my position on some of Ed’s edicts softened. I came to understand that a good ad doesn't have to make you feel like a schmuck after all, although I still maintain that it does have to make you feel. But god damn it, I held onto that exclamation point rule.

In retrospect, I was like a carpenter who refused, on principal, to use needle nose pliers, even once in a while when you couldn’t get the claw end of a hammer into that tiny space up under the eaves to remove a staple from the old siding because Jesus said not to use them, never mind that Jesus probably wasn’t the kind of carpenter who had call to renovate a Portland four square.

Back to my birthday.

You know how kids are. They pile on top of you, get all excited to give you the best birthday present in the history of birthday presents, and then suddenly they’re off making an art project out of dust bunnies while you sit there, wondering whether it’s okay to take the chicken costume off now because it makes your nose sweaty. If you’re me, you do. And then you log onto Facebook in hopes of finding something, anything, that will prolong the incredible birthday love rush.

And there it was. A birthday greeting. Three words:

Happy birthday, Brian!

From Ed.

McCabe.

I try not to swear when the kids are around but I’m pretty sure I used the F word. That’s okay, though, because dust bunny art requires intense concentration and they probably didn’t even notice.

To say this was a big deal was kind of an understatement. This was a big deal!

Here was Ed himself telling me that it was okay.

That was three years ago today. Today, on the anniversary of that birthday, I want to give the gift to you.

If you shared my obligation to avoid exclamation points, I hereby release you. Let it go.

Not because I said it's okay or even because Ed said it's okay, but simply because we are in the business of communicating and the reason we have rules at all is to guide us, not constrain us.

The point is, do what works. And by the way, a really good way to figure out what works is to know your audience and genuinely care about them. I gotta believe that's what got my kids to come up with the chicken costume in the first place.